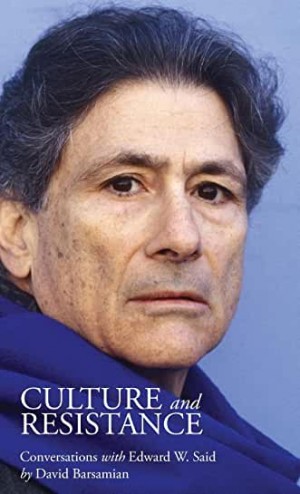

Edward W. Said was University Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University and the author of more than twenty two books. A member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the Royal Society of Literature and of Kings College Cambridge. A leading literary critic, public intellectual, and passionate advocate for the Palestinian cause, he was born in Jerusalem in 1935 and died in New York in 2003.

Said’s father, Wadie (William) Ibrahim, was a wealthy businessman who had lived some time in the United States and apparently, at some point, took U.S. citizenship. In 1947 Wadie moved the family from Jerusalem to Cairo in order to avoid the conflict that was beginning over the United Nations partition of Palestine into separate Jewish and Arab areas . In Cairo, Said was educated in English-language schools before transferring to the exclusive Northfield Mount Hermon School in Massachusetts in the United States in 1951. He attended Princeton University (B.A., 1957) and Harvard University (M.A., 1960; Ph.D., 1964), where he specialized in English literature. He joined the faculty of Columbia University as a lecturer in English in 1963 and in 1967 was promoted to assistant professor of English and comparative literature. His first book, Joseph Conrad and the Fiction of Autobiography (1966), was an expansion of his doctoral thesis. The book examines Conrad’s short stories and letters for the underlying tension of the author’s narrative style; it is concerned with the cultural dynamics of beginning a work of literature or scholarship.

Said was promoted to full professor in 1969, received his first of several endowed chairs in 1977, and in 1978 published Orientalism, his best-known work and one of the most influential scholarly books of the 20th century. In it Said examined Western scholarship of the “Orient,” specifically of the Arab Islamic world (though he was an Arab Christian), and argued that early scholarship by Westerners in that region was biased and projected a false and stereotyped vision of “otherness” on the Islamic world that facilitated and supported Western colonial policy.

Although he never taught any courses on the Middle East, Said wrote numerous books and articles in his support of Arab causes and Palestinian rights. He was especially critical of U.S. and Israeli policy in the region, and this led him into numerous, often bitter, polemics with supporters of those two countries. He was elected to the Palestine National Council (the Palestinian legislature in exile) in 1977, and, though he supported a peaceful resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, he became highly critical of the Oslo peace process between the Palestine Liberation Organization and Israel in the early 1990s.

His books about the Middle East include The Question of Palestine (1979), Covering Islam: How the Media and the Experts Determine How We See the Rest of the World (1981), Blaming the Victims: Spurious Scholarship and the Palestinian Question (1988; coedited with Christopher Hitchens), The Politics of Dispossession (1994), and Peace and Its Discontents: Essays on Palestine in the Middle East Peace Process (1995). Among his other notable books are The World, the Text, and the Critic (1983), Nationalism, Colonialism, and Literature: Yeats and Decolonization (1988), Musical Elaborations (1991), and Culture and Imperialism (1993). His autobiography, Out of Place (1999), reflects the ambivalence he felt over living in both the Western and Eastern traditions.

Besides his academic work, he wrote a twice-monthly column for Al-Hayat and Al-Ahram; was a regular contributor to newspapers in Europe, Asia, and the Middle East; and was the music critic for The Nation. He was also the editor, with Christopher Hitchens, of Blaming the Victims, published by Verso. Said was also an accomplished musician and pianist.

In his final years, Said's health grew ever more fragile, and, though passionately concerned with the unfolding Palestinian disaster in the wake of 9/11 and the Anglo-American invasion of Iraq, he took a conscious decision to withdraw from political controversy and channel his energies into music. The West-Eastern Divan Orchestra he founded with the Israeli citizen Daniel Barenboim in 1999 grew out of the friendship he forged with the musician who shares his belief that art - and, in particular, the music of Wagner - transcends political ideology. With Said's assistance, Barenboim gave master classes for Palestinian students in the occupied West Bank, infuriating the Israeli right.

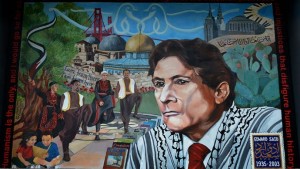

In 2004, one year after he passed away, the Edward Said National Conservatory of Music was established in Ramallah and other Palestinian cities, and the city of Ramallah named a street after him.

Edward Said received many awards, honors, and prizes, among them the Lionel Trilling Book Award (1976); Sultan Oweiss Award (1996–97); the Lannan Literary Prize for Lifetime Achievement (2002); and (with Daniel Barenboim) the Prince Asturias Award for Concord (2002). He received numerous honorary doctorates and was most proud of the one he received from Birzeit University in 1993. He was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and a board member of International PEN.

As war rages in Gaza, twenty years after his passing, the scholar and activist’s words still ring true as so little has changed. In An Open Letter to American-Jewish Intellectuals, composed in 1989 he wrote

“I cannot understand how raw, naked evidence can be overridden by American intellectuals just because the ‘security’ of Israel demands it.

…

But it is overridden or hidden no matter how overpoweringly cruel, no matter how inhuman and barbaric, no matter how loudly Israel proclaims what it is doing. To bomb a hospital; to use napalm against civilians; to require Palestinian men and boys to crawl, or bark, or scream ‘Arafat is a whore’s son’; to break the arms and legs of children; to confine people in desert detention camps without adequate space, sanitation, water or legal charge; to use teargas in schools: All these are horrific acts, whether they are part of a war against ‘terrorism’ or the requirements of security. Not to note them, not to remember them, not to say, ‘Wait a moment: Can such acts be necessary for the sake of the Jewish people?’ is inexplicable, but it is also to be complicit in these acts. The self-imposed silence of intellectuals who possess, in other cases and for other countries, supremely fine critical faculties is stunning.”