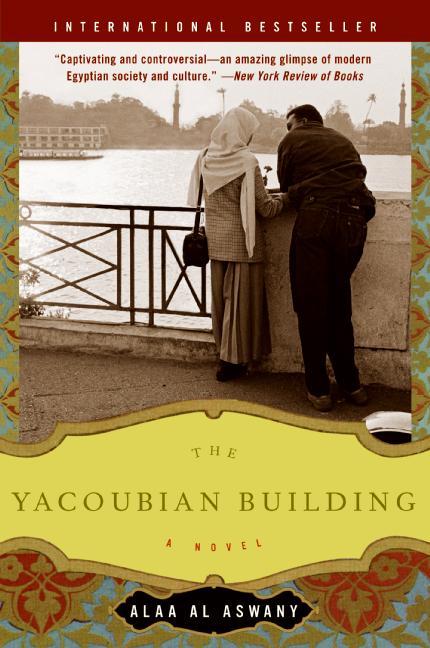

'Imarat Yacqoubian (The Yacquoubian Building), Alaa El-Aswani, Cairo: Miret, 2002. pp348

Reviewed by Amina Elbendary

Al-ahram Weekly 13-19 June 2002

Amidst what the literary periodical Akhbar Al- Adab has termed the "fictional explosion" currently taking place in Egypt, Alaa El-Aswani's first novel, 'Imarat Yacqoubian, stands out. The author, a dentist by profession, has also written two collections of short stories, and this book is similarly approachable, even as it touches on dangerous territory. This is a novel to sit down with on a summer afternoon, cup of coffee at hand. Familiar in structure, strongly reminiscent of Naguib Mahfouz's tale of life in an Alexandrian pension, Miramar, the novel tells the story of the inhabitants of the Yacqoubian Building, built in 1934 by an Armenian-Egyptian businessman on Soliman Pasha Street in downtown Cairo, a place where many lives intersect. As the reader soon discovers, this building has many aspects -- spatial, architectural, intellectual, political and textual. At the time when the novel is set, both before and shortly after the 1952 Revolution, downtown Cairo, wast al- balad, was the centre of the city. Since then, both the city and the building have greatly changed, as has the middle-class whose members would once have lived there, changes that the novel both acknowledges and laments. The building's tenants change after the Revolution, army officers moving into flats abandoned by the former elite and foreign businessmen. Now, in a twist of the traditional upstairs-downstairs tale, the real "downstairs" -- the porter's family, the urban poor -- occupy the former servants' quarters on the building's roof, now developed almost into a shanty town, with the lives of the middle class residents of the flats in between providing much of the interest of the narrative. However, the novel, though set in Cairo, extends well beyond this downtown building, exploring the geographical and political corners of the Egyptian scene and looking back on post- revolutionary events from the perspective of the early 1990s, just as the Gulf War was erupting. The comparison with Mahfouz's Miramar again comes to mind, for much as does the pension in the Nobel Prize winner's novel, the Yacqoubian building here serves as a kind of national locus, the lives of the building's inhabitants adding up to something like the Alaa El-Aswani's History of Modern Egypt. Like the novel's form, this is history traditionally told, connecting money, power and corruption and bringing together wealthy businessmen, corrupt officials and militant fundamentalists, with little in the way of innovative analysis. The characters include Zaki Bey, son of a pair of wealthy aristocrats and graduate of a Western education. A bachelor in his mid-sixties, Zaki is a womaniser, his life revolving around women and sex. Then there is Taha El-Shadhli, the porter's son, a candidate for the title of Egyptian Everyman, an ibn al-balad struggling to prove himself through education and working his way up the social ladder only to be pushed back down because of his father's occupation. His dream of entering the Cairo Police Academy and marrying his sweetheart, Buthayna, is shattered. Buthayna, one of the novel's many female characters, lives on the building's roof, has to work to support her brothers and sisters, and is eventually driven to providing her boss with favours in return for cash. Later employed by Zaki Bey, she embarks on an affair with him that is probably the most humane relationship in the novel, even though it is one between a young woman in her twenties, at first obliged by economic necessity, and an old man in his sixties who, in the social hierarchy of the time, would have been considered far and away her social superior. Another character, Hatem Rashid, comes from a socially mixed marriage and is editor-in-chief of a French-language Cairo newspaper, Le Caire. A homosexual and member of the city's Westernised elite, Hatem had been initiated into homosexuality by a family servant when a young boy, and as an adult he continues to cross social and sexual boundaries by having an affair with Abdu, a Nubian conscript, who is married with a wife and family. Hatem helps Abdu set up a kiosk to earn a living. Meanwhile, there is also Soad, a poor woman whose husband has gone missing and has been left with a son to bring up. She goes to court to annul her marriage, remarrying Hagg Azzam, a much older businessman with adult children, who demands that their marriage remain a secret and that she have no further children. Evidently, these characters play symbolic roles, the reader identifying them with the stock figures of Egypt in the 1950s. Thus, Zaki Bey is the aristocrat, a remnant of the pre-revolutionary regime, Hatem Rashid is the Westernised homosexual, Taha is the lower middle-class, frustrated young radical and Buthayna the single woman whose life-options are narrowed by her situation. In the main, the author has fleshed out these unpromising stereotypes, with the exception of Hatem Rashid, who is presented so negatively, his affairs being the excuse for frequent asides on homosexuals in general, that one questions the sincerity of El-Aswani's inclusion of the traditionally marginalised in his narrative. While all the characters in the novel are in one way or another condemned, perhaps only Taha El-Shadhli escapes the general condemnation, receiving a measure of authorial sympathy. Hard working, upright and studious, Taha is denied opportunity as a result of his social background, never managing to rise. Nevertheless, here too a suspicion of the stereotype creeps in, for it is from Taha's background that radical Islamists are considered traditionally to come, the novel teetering here on the edge of soap-opera. Joining a militant political group as a result of his frustration, Taha gets involved in operations against senior state and police officials, eventually being hunted down by the authorities in one of the novel's most dramatic scenes. The novel is inclusive, opening a space for people from different walks of life and presenting them together in this microcosm of the city without being a novel about the margins alone. Nevertheless, even as such people are formally included in the narrative, societally they are largely doomed, their power over each other being largely destructive and any changes brought about being mostly damaging. The poor are exploited by the affluent, either sexually, as is Buthayna by her boss, or as Abdu is by Hatem Rashid, or economically. When Soad rebels against the unjust conditions of her marriage and becomes pregnant, Azzam forces an abortion on her, and later a divorce. When Abdu ends the affair with Hatem Rashid, he is left penniless. 'Imarat Yacqoubian is thus largely a story of oppression and exploitation, a story of power and its abuse. None of Alaa El-Aswani's characters is shown succeeding in life. There are no success stories in this book, and Taha, who tries to better himself and rise above the chaos that reigned over his youth, is killed by the police, accused of being a terrorist. Perhaps, therefore, by the end of the novel the reader will have lost all appetite for coffee, that summer's afternoon having significantly darkened. Nevertheless, the novel closes with Zaki Bey and Buthayna getting married at a simple wedding reception: perhaps even El- Aswani could not put down his pen without giving some form of farah (happiness) to his readers, if not quite of amal (hope).