First Published Almanassa News May 14, 2025

I can’t claim any personal closeness to Sonallah Ibrahim. He’s reclusive, and I’m semi-reclusive myself.

In my twenties, I found myself among the 60s generation of writers by coincidence, who were in their fifties. I knew no other generation, didn't know much about the lives of authors my age, nor did they know much about me.

However, Sonallah wasn’t among those I knew.

From stories they told me, I gathered how fiercely he defended his solitude—or rather, how he defended his time. Many of his peers were spontaneous in their youth, knocking on each other’s doors after midnight to chat or crash for the night. Some even stayed for days until the original tenant was nearly forgotten.

As they settled into middle age, their meetings became more restrained, but they still joked about Sonallah’s rigid stance against the carefree nature of youth—like the time he turned away someone who had come to visit without notice.

The solitude of creation

Stories like that made it difficult for someone like me to even consider disturbing the recluse. Still, I often wanted to reach out to express my admiration when a new book of his came out.

Sometimes I felt an overwhelming urge to express my gratitude, because, after Naguib Mahfouz, Sonallah made me realize that loyalty to the text matters infinitely more than the social aspects of the literary scene.

Over the last fifteen years, stolen from both our lives and Egypt’s, I was more than willing to visit him just to check on his health, provided I could do so under the wing of someone close to him. But it never happened.

Now I’m shaken to hear that he’s ill. I can’t picture old age overtaking the man whose eyes always seemed alert behind those oversized glasses that looked like they were part of his face. They never changed in style. Perhaps they are what made him look like an eternal child.

Yet, such is the relentless march of time: humanity’s wound. Sonallah understands this, as do all true artists, for no one has written, painted, or sculpted without trying to ease the ache of that wound.

From our wise Egyptian forefather Ipuwer to Homer and Cervantes, everyone who challenged time knew the ultimate outcome. But they bravely fought on and left their mark on its body, and that, in itself, is an honor.

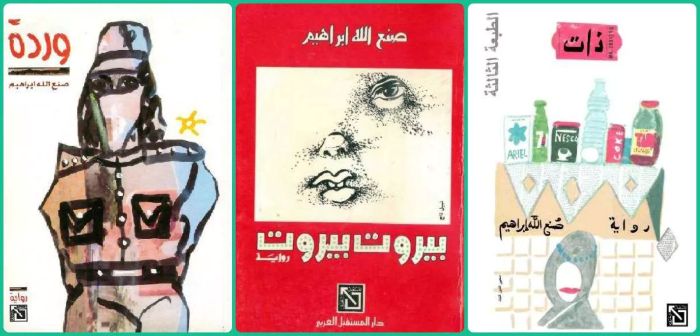

Sonallah is one of those brave souls. Through his magnificent self-sufficiency and long solitude, he experimented with literary pathways, pushing the limits of documentary narrative in “Zaat”, delving into the nightmarish in “The Committee”, and drawing on political and human experiences beyond Egypt, as in “Beirut Beirut” and “Warda.”

Each of his books bears his imprint. Each release ignited political and literary debate, true to his belief in the role of literature, even as the world around him leaned toward depoliticized fiction, that is entertainment fit for the consumer age, exportable across borders like multinational products.

As a reader of Sonallah, I have a treasure trove of his books. The crown jewel is “That Smell and Notes from Prison,” his debut novel from 1966. It has always felt fresh to me, with a biting language that sparked outrage at the time but perfectly suited its theme. That angry tone matched the foul stench of repression and defeat that followed.

Every act of repression drags behind it a terrible defeat. Always!

From that same precious collection, I treasure “Yawmiyyat al-Wahat” (Diaries of Oasis Prison), which I consider one of the most tender accounts of prison life. It offers not just a chronicle of political incarceration under Nasser, but captures the making of a young man who decided, while imprisoned, to become a writer.

The brilliance of the book lies in its portrayal of prison as an almost ordinary place. The narrative is not devoid of pleasures. This finds its most recent echo in Ahmed Naji’s “Rotten Evidence.”

Glimpses of a lost world

Then there’s “The Stealth”, which I’ve returned to twice since its release, partly to recall my own childhood, and partly to understand things I no longer grasp. Sonallah never lets go of his political vision, not even in dreams, I suspect.

The novel takes us through the 1930s and 1940s, complete with its conflicts and prejudices. Avoiding heavy-handed documentation, it invites us to savor the art of observing life through the eyes of a child. The adjustment of the narrative to his level of understanding is both delightful and deeply sensitive.

The bond between the boy and his father, who is ambling toward his second childhood, is tender, replete with affection, mischief, sympathy, and sometimes anger. The novel is saturated with details that engage the senses.

Sonallah resurrects Cairo of that era through sounds, colors, and smells, using delicate cues that reveal a pristine sensory memory. The detail of a woman sitting before a tray full of cigarette butts feels fleeting, yet unforgettable.

In his foreword to Hindawi Foundation’s free online edition, Sonallah recalls buses divided by a glass barrier into two classes. As a boy, he’d watch the first-class passengers with envy. He rejoiced in this cultural initiative that, in offering “The Stealth,” broke down such barriers between classes of readers.

Gandhi of the novel

After the oversized glasses that never quite fit his face, “The Stealth” only deepened the Peter Pan image I hold of Sonallah Ibrahim, the mischievous boy who never grew up.

Fittingly, those very glasses appear in the opening scenes of the novel, during a bus ride through Cairo. Arriving in Sayyida Zeinab, the young protagonist wanders through a marketplace alive with sellers of second-hand goods. He picks out his pair from a pile of used glasses laid out on sheets of newspaper, sold by a man wearing a broken pair held together with a tin strip.

Later in the novel, he mentions that those glasses earned him the nickname “Gandhi.”

I wouldn’t be surprised if the glasses he wears today are the same ones he bought that day, hand-in-hand with his father.

In that same personal canon, I place his 2017 novel “67”, which languished in a drawer for nearly fifty years. It’s the spiritual twin of “That Smell.” In the latter, we sense the stink of defeat. In the former, we swallow its bitterness. “67” didn’t spark the same controversy, perhaps due to the cultural deadening that followed the failed uprisings of the Arab Spring.

In the novel’s preface, Sonallah Ibrahim recalls writing it in 1968 while in Beirut, originally under the title “1967.” He recounts how Beirut publishers, including Nizar Qabbani’s own imprint and Dar Al-Adab, rejected the manuscript. Suheil Idris of Dar Al-Adab reportedly dismissed it on the grounds that the protagonist was too consumed by sex.

Sonallah admits that, after his time in Beirut, he became distracted by travel.

As Sadat’s political shift began to take hold, Sonallah made a deliberate decision not to publish the novel, fearing it might be used as ammunition by the right against Nasserism and socialism. That choice stands as yet another enduring lesson in principle.

The forgotten soul

It’s a slim novella of twelve chapters, spanning the months of the fateful year. It opens with a New Year’s Eve party full of alienation and meaningless social interactions, relationships steeped in ennui and sexual frustration rather than intimacy or passion. The sixth chapter marks the arrival of the June defeat.

The disaffected narrator in both novels becomes an unforgettable example of the neglected human being. Defending that forgotten figure of a man is the core of Sonallah’s project, both literary and political. And even if we forget everything else he did, even his prison years, we can never forget the moment in 2003 when he rejected a state-sponsored prize for the novel in a searing political speech at Cairo Opera House.

It was perhaps the boldest slap to Mubarak’s regime, a foreshadowing of the resistance that would erupt years later.

The searing words he managed to deliver that night marked the apex of Sonallah Ibrahim’s life, as both a writer and a human being. The regime was shaken, and the cultural elite split into supporters and critics. The “enclosure,” as Farouk Hosny once called it—may God have mercy on those days—was larger than the free space outside it, so condemnation was widespread. But to be fair, feelings weren’t so clear-cut.

An esteemed Arab critic, who served on the award’s jury and had strongly advocated for giving it to Sonallah, told me that night: “He spat in all our faces.”

It took me time to grasp the meaning of that sentence, because it held more admiration than reproach, and not a trace of anger.

I believe the debt of that spit upon our faces can only be repaid with a kiss on the head—and two on the forehead—out of love and respect for Sonallah.