Amir Bibawy

Special to the Middle East Times

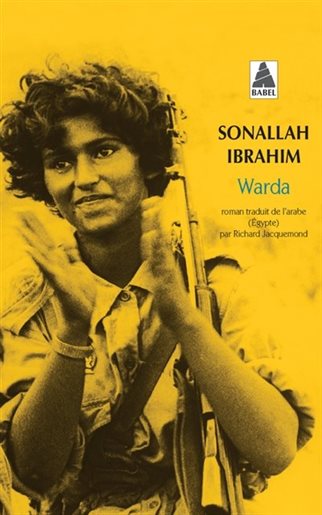

Sonallah Ibrahim's latest novel, Warda, comes at a time when the literary output of Egypt is at an all-time low. Controversial works of fiction that have been banned in Egypt have led to an alarming decline in the number of books published in the country. Perhaps this is why Ibrahim states at the outset of his new novel that while his characters are drawn both from reality and from his imagination, the novel should be read as a work of fiction. Ibrahim's novel, his first in three years, revolves around the protagonist Rushdie, a writer, who visits his cousin Fathi in Oman. Rushdie is in Oman to look for an Omani friend of his whom he has not seen in over 30 years. With only the man's first name, Yaarub, the search seems impossible. But an improbable series of events unfolds and Rushdie, a devout communist, finds himself caught up between Oman's ruling elite and the remains of the outlawed communist and revolutionary movements. As the plot develops, the revolutionaries hand over a stack of notebooks to Rushdie written by the sister of his lost friend Yaarub. Ibrahim's novel is named after Yaarub's sister. Rushdie had been infatuated with Warda in the 50s when they had all lived in Cairo. The sister herself was part of the Omani revolutionary movement and has left her diaries for only Rushdie to read. Through the diaries, Ibrahim uses his unique style of what has come to be known as the documentary novel. The diaries serve not only as a personal journal but also as a document that chronicles the events that took place in the Arab world between 1960 and 1975. Excerpts from books, newspapers, and speeches by political leaders such as Gamal Abdel Nasser and Fidel Castro are part of Warda's diaries and of Ibrahim's own communist rhetoric. Rushdie later finds out that Warda gave birth to a daughter while she was involved in the revolutionary struggle against the British in Oman as well as Oman's ruler, Sultan Said. Warda's daughter has had the diaries for years and knows that she can only give them to Rushdie when he, by a mere and unlikely coincidence, turns up in Oman. Rushdie later on meets Waad, the daughter, and, ironically, sleeps with her, which could only be called a far-fetched fantasy on behalf of the author. It is through this fantastical plot that the protagonist finally realizes what had happened to both his friend and his sister Warda during the previous years. Warda has not added any new development to Ibrahim's previously published work of six novels and a dozen children's books. It could well be considered the third volume of a trilogy where the protagonist is a writer. The first one, Al Lajna (The Committee) published in 1981, is about a writer who is fiercely interrogated by a committee concerning the publication of his work. The satirical novel ends in the writer biting his arm and eventually eating himself! The second book in the trilogy is Beirut Beirut (1984), a novel about an impotent writer who visits Beirut during the civil war and is commissioned to write a commentary for a war documentary. The novel is the fourth in Ibrahim's line of documentary novels that employ a literary style unique in Arabic writing. The other three are Beirut Beirut Zat (1992) and Sharaf (1997). More than half of each of Ibrahim's documentary novels comes from sources such as newspaper clippings, speeches by politicians and excerpts from well-known books. Readers are often tempted to skip those uneventful parts but eventually find out that the remaining part of the novel cannot be properly understood without them. Ibrahim's most accomplished work to date remains his first novella Tilka Al Raiha (The Smell of It) published in 1966, which he wrote after spending several years in one of Nasser's many political prisons. The novella paved the way for the emergence of a new style of Arabic literature which relies less on wordiness and more on emotions and feelings. Because of its strong political messages, the novella was banned immediately after publication and was unavailable for 10 years. What Warda does offer to the reader, however, is Ibrahim's unique writing style. His prose is concise and tightly-packed. It includes his usual allusions to homosexuality and detailed descriptions of the protagonists' sexual escapades. It also provides a deep analysis of Oman's politics and revolutionary movements which could well have taken Ibrahim years to study. Oman, which is not often in the media spotlight, appears to the reader of Warda not only as a country with a rich tradition and heritage, but also the scene of a violent power struggle between its different political factions. Warda, which has only been on for sale for just over a month, may yet bring a strong Omani government reaction because of its open critique of politics and human rights in the Gulf state.