Samia Mehrez reads through Somaya Ramadan's multiple layers of narrative

Al-Ahram Weekly Online 20 - 26 December 2001

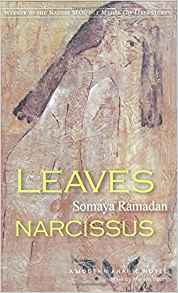

After two successful collections of short story, Somaya Ramadan published her first novel Awraq Al-Nargis (The Narcissus Leaves) in 2001, a pseudo-autobiographical narrative that won her not just instant acclaim within Egyptian literary circles but the AUC Naguib Mahfouz Literary Award as well. In a recent interview conducted with her, Ramadan explains the tardy arrival of her first novel through a contextual relationship with the decade of the nineties: "The time had come when I could write about myself. The nineties provided the time and the place for people to write about their individual selves. So I became more confident that what I had written would not be strange or inappropriate. Maybe if I had published it earlier it would have gone by unnoticed. There is always a point of congruence between the writer, the [historical] moment and the content [of the work]." Somaya Ramadan's moving depiction of her protagonist's parenthetical madness in Awraq Al- Nargis confirms and expands the frightening rupture between the individual and the collective that has become the distinguishing mark of many works of the nineties. Awraq Al-Nargis revolves around Kimi, the narrator whose life unfolds before the reader in a series of dislocated, dialogical sequences, written in densely rhythmic language that places this mature work within the category of the prose poem. At the heart of these sequences, is the ever-lingering question "How is it possible for one to understand?" This is the question that Kimi re- asks as she repeatedly attempts to write her 'papers', making of the question a central, anguished one for herself and for her reader. In Awraq Al-Nargis, life, its meaning, and its representation are no longer linear, causal, or logical as so many earlier texts had depicted them. Rather all has become "parallel, parallel" as the narrator of this labyrinthine text reminds us throughout. Just as Kimi writes and rewrites moments of herself in order "to understand," so too does the reader read and reread in a parallel, frustrating, attempt. Just as the beginnings of the text are multiple, so too are its levels of reading. This multiplicity is accentuated in the narrative through the key word that is the title of the first chapter, punctuates the entire text, and finally appears as the very last word: "perhaps" (rubbama). The repetition of the word "perhaps" intensifies the quest for understanding (of the self and of the world) and provides the narrative with its spiral, open-ended, quality. "Perhaps" becomes the key and ultimate answer in the text. The narrative therefore remains suspended from beginning to end, it remains incomplete, on the threshold of knowledge/ignorance, saneness/madness, life/death, all of which remain "parallel, parallel." The text opens with the disturbing statement: "The moment before surrender is the most difficult." The narrator, who throughout the text alternates between the first person and the third person points of view, proceeds to unravel this central story of resistance and surrender: "No sooner does the capsule enter my mouth than I spit it out. It is a small capsule, with it you will go into deep sleep. This is all that is required. My friends require it, my siblings, and my mother. My closest of kin conspire kindly. After that you will go into deep sleep. Then, negotiations begin. I exhaust them...They all become the angels of death." From the start, we are immersed in a warlike situation where the narrator is resisting alone the "kind" conspiracy of the world against her, a world united like the "teeth of a comb," constituted by the "wise" members of her family and her closest friends. When she finally swallows the small pink capsule her body is flooded with signs of very slow death. In preparation for that death, she recites her own shahada as "they" had taught her: "The kingdom of the Lord is forthcoming, and there is no God but Allah, and the wise ones around me smile. Now I have their blessings and they have mine. The peace of surrender prevails. "By God I testify: I have done everything I can. I have resisted with all my will power and have held on until the very last moment, even as I watched my mind take flight, and I did not give up. If I have not understood, it is not because I was lazy but because good and evil are beyond my comprehension." Even though Awraq Al-Nargis begins with "the moment before surrender," the reader quickly understands that this is but one of the possible beginnings to Kimi's parallel episodes of resistance. In one of those possible beginnings, Kimi, like Shehrazad, tells another version of her own story: "Once upon a time there was an intelligent, sharp, clean girl. Innocent to the point of naivet� at times. She had read many books. But we spared her experience so we did not allow her to suffer. We provided everything for her. And when she wanted to continue her education, we sent her to a respectable university in a conservative Catholic country. We constantly monitored her good behavior through an honorable Arab professor who chose for her a field of specialisation, at a university he often visited... A conscientious girl, obedient and respectable. She never once upset anyone. She went to the library and came back to her room to read. She finished her studies within due time and returned home. We are very proud of her and expect a lot from her." Kimi writes this perfect fairy tale as imagined and told from the point of view of the "kind" conspirators, the members of her family. This account is juxtaposed against her own nightmarish version of the same fairy-tale. When she returns to Egypt her family chooses to block out the episode of her "madness" in Dublin in order to preserve their fairy tale at her own expense. The juxtaposition on the same page bespeaks an unbridgeable gulf between Kimi and her immediate world, what was expected of her and what she has become. Her sense of loneliness and isolation is reflected on many levels throughout the narrative: "I did not notice them as they constructed this huge, thick bell jar around me...What had I done for them to isolate me so?" As a child, Kimi makes a constant effort to remain within the boundaries that are set for her, however, her fear of failure continues to haunt her: "Judgement is on the Day of Judgement, as in the religion lesson. On the Day of Judgement people are made to walk on a tight hair. Those who are good fall into paradise, those who are bad fall into hell. My only concern was not to fall. And judgement was a daily thing." Kimi's daily trip to school as a child encapsulates this lifetime experience. She walks to school carefully balancing her feet on the edge of the sidewalk by way of "perfecting self-discipline" and remains engulfed with the fear of falling from "the straight path." On her way home she falters and can no longer walk on the edge: "I realize that it is fear of error. The possibilities of error are endless, infinitely endless. No one notices and no one remembers but I." She is taught "precision, order, cleanliness and self-discipline." At home voices must not be raised. Calm is of absolute importance. As a teenager she is reprimanded: "You spoke, you looked; you laughed louder than you should. You were too informal when you shouldn't have been, you did not keep your thighs tightly held, you ate with gluttony, you gave your opinion in matters that do not concern you, you butted in on a conversation, you were conceited, you were aloof." And more importantly, the repeated advice/ premonition from Amna, her nanny "Don't look at your face in the mirror. Those who look at themselves in the mirror for too long, go mad." Eventually, Amna's advice becomes one of the recurring leit-motifs in Kimi's story of madness/ awareness. In Dublin Kimi secludes herself in her room at the hostel, she speaks to no one and no one speaks to her. She writes but no one reads her. She comes to be known as "the strange woman" and is likened to Sylvia Plath by the Dublin dorm residents. On her wall is a map of exile. Not of her own homeland, Egypt, but rather of her "imagined homeland" and refuge -- "posters of James Joyce, Samuel Beckett, a confused Chinese woman at a crossroads, an old man looking out desperately at sea." To these landmarks of her imaginary homeland she adds Salvador Dali's Metamorphosis of Narcissus, the image responsible for her own metamorphosis. Dali's poster on Kimi's wall becomes her looking glass: the dismembered human figure, the glasslike lake, and the narcissus flower itself, all send her on her own Narcissus journey and her first moment of awareness/madness, resistance/ escape through writing, culminating in The Narcissus Leaves (Awraq Al-Nargis): "This was the moment when the minute crystal threads that constituted the bell jar began to slip...Wake up. Come out from under that bell jar. Write me. Only you can. Only you can save me." Flashbacks of Kimi's relationship with her mother reinforce her sense of loneliness and alienation. She describes her mother sitting in the winter sun on the balcony with her sewing box: "I sit watching her on the opposite chair. And when I speak to her she does not reply. Between us stands an erect wall of cut glass that allows only images, and not voices, to glide through. I remain silent and watch." The rift between the mother and the daughter takes on dramatic proportions when the mother fails/refuses to see the reality of Kimi's breakdown: "Why do you insist on nullifying me? Why don't you ask me whether I want to go to the beach with them? "Because every time you go you come back and spend days staring at the ceiling. The absent mother is juxtaposed against Dada Amna's strong presence. Whereas the mother's voice is seldom heard, "Amna's is clear and strong." Kimi completely identifies with her nanny, Amna. Indeed, Kimi's mother describes Amna as being "stupid," the same adjective used by Miss Diana, the arithmetic teacher, to describe Kimi. Amna is also seen as "stubborn, like a mule" not so different from Kimi who's head is pounded by Miss Diana on the glass of the dining table splitting it in two. Amna is Kimi's alter-ego: she is the illiterate, peasant woman whose oral, popular mythology is braided into Kimi's Greek and Western myths and stories that resonate throughout the narrative. Towards the end of the text, the scent of oranges that accompanied the mother's presence is displaced onto Amna: "My mother, my mother is the scent of oranges. How has Amna come to possess my mother's scent?" The climax of Kimi's identification with Amna occurs when she wrestles against her "satanic" self that refuses to accept the peaceful death of the small pink capsule. Rather than command the death of the self, the "I" (ana), Kimi inserts an "m" into the word thereby commanding the death of Amna within her: -Die "I"! -Die "I"! Or am I saying: -Die Amna! However, Kimi survives this imposed death through her repeated attempts at writing. It is in the process of writing and rewriting that she kills all the 'kind' others, only to discover that writing "is never complete" for "how can anything be complete except if it dies?" Writing therefore becomes her way of "becoming what she wants," her way of defying non-meaning, and her hope to start life anew: "Many pages were torn over three days, pages that were no good. A Lie! It's just that I didn't know that they were any good. The thing was, they were written in English." "I killed them, all of them, in three days. I wrote them and then I shredded them when their breath overtook the air in the room and swallowed it leaving me without any breathing space." "And before all else I cut Kimi into fourteen pieces. I threw her mutilated body into the wastebasket." Reading Awraq al-Nargis is the process of collecting Kimi's mutilated body, the attempt to paste together the various shredded pieces of the story that has been written and rewritten. One of the recurrent leit-motifs in Ramadan's text is the image of her mother's pair of scissors that has lost the middle screw that allows the hands of the scissors to create new life and to generate new meaning. The lost screw has rendered things "parallel, parallel. Today, Nothing happens in my father's house," says Kimi, a situation that is mirrored outside that house: "Mr President, Mr President, Mr President, and flowers in a tall crystal vase, two arm-chairs and a table. And nothing happens, not in our house or in anyone else's... parallel, parallel, parallel." But despite all this, Kimi resists and writes with the conviction that "Poets write from the vantage point of the little screw that allows the hands of the scissors to create meaning." Finally, it is important to note that the diminutive name of the protagonist Kimi is very close to the word Kimit that denotes Egypt (the black earth) in ancient Egyptian. It may therefore be said that Kimi's search for meaning on a personal level, through writing, is also a search for a collective one, "perhaps."